Signal carriers from cells embedded in tissue send short-range messages

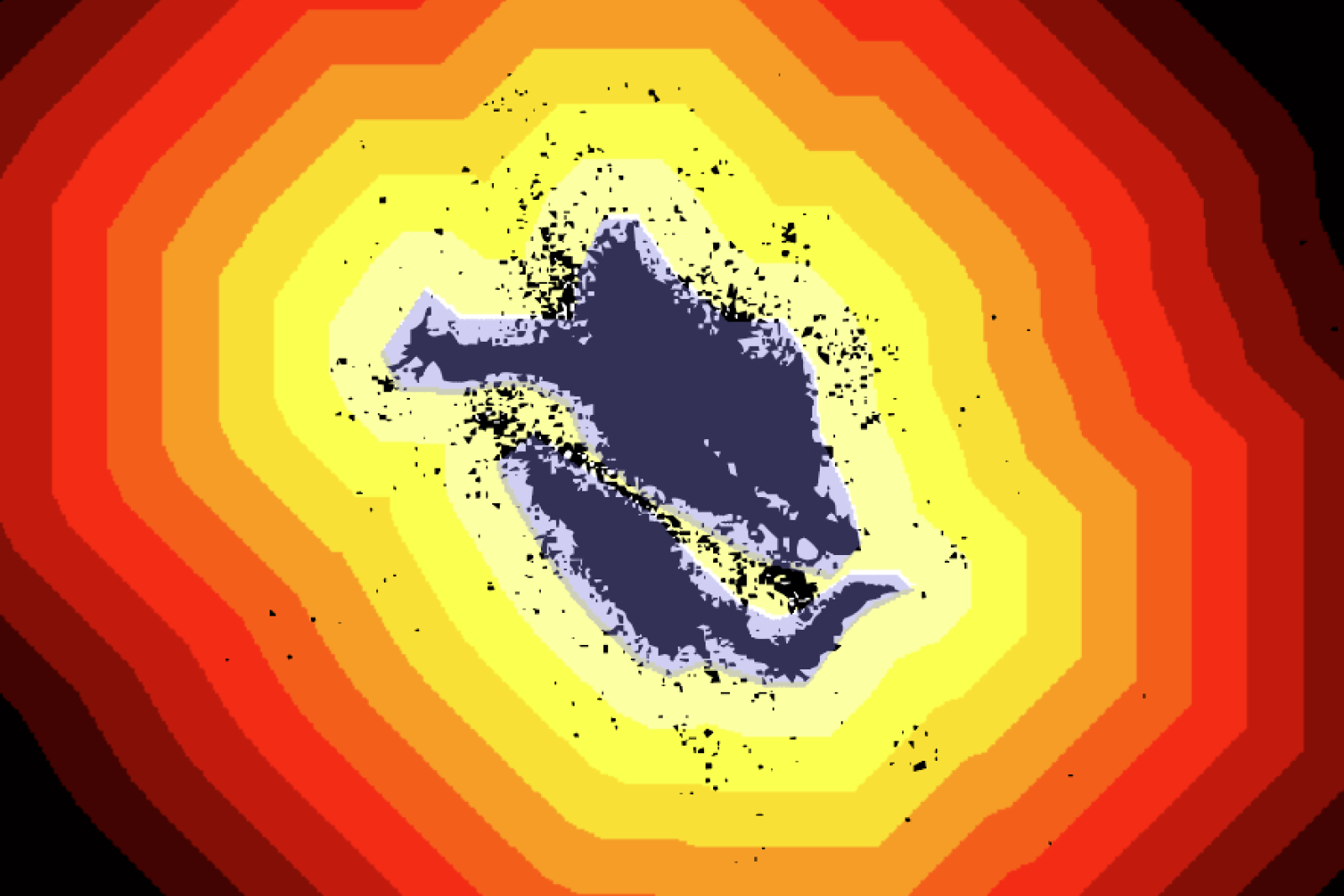

Researchers created a mathematical visualization of extracellular vesicles’ movement, showing that most particles traveled no farther than about 50 microns from the edges of the central donor cell.

By Emily Caldwell, Ohio State News

A new study may change the way scientists think about the distance traveled by tiny bubbles carrying signals between cells that are embedded in tissue.

These particles, called extracellular vesicles, are known to safely carry signaling cargo as a communication method between cells in bodily fluids and within tissue, and to influence health and disease. Understanding how the properties of these vesicles differ in normal versus diseased tissue could make them outstanding biomarkers for early disease detection, researchers say.

Scientists at The Ohio State University have made inroads into understanding one side of that equation, finding that extracellular vesicles’ range of travel in a cancer tumor environment is limited almost entirely to nearby recipient cells – which is related to how densely packed cells are in a tumor.

“This is the first assessment of how far a vesicle can move in physiological conditions. We didn’t perturb the system. We just measured on a single-cell basis how far a vesicle can go,” said senior study author Emanuele Cocucci MD, PhD, associate professor of pharmaceutics and pharmacology at Ohio State, who is studying these particles – and how physiological conditions affect them – to weigh their potential as biomarkers for pancreatic cancer.

“This is the first assessment of how far a vesicle can move in physiological conditions. We didn’t perturb the system. We just measured on a single-cell basis how far a vesicle can go,” said senior study author Emanuele Cocucci MD, PhD, associate professor of pharmaceutics and pharmacology at Ohio State, who is studying these particles – and how physiological conditions affect them – to weigh their potential as biomarkers for pancreatic cancer.

“There are no clear biomarkers for pancreatic cancer at the moment. Our goal is to define a novel biomarker,” said Cocucci, also a member of the Leukemia and Hematologic Malignancies Program at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center. “But until we know how extracellular vesicle exchange occurs in tissue before and during cancer onset, it’s impossible to understand whether extracellular vesicles could be the next answer for early diagnosis of pancreatic cancer.”

The study was published recently in the Journal of Extracellular Vesicles.

This work involved a series of cell culture experiments in two cancer cell types, first showing that increasing the density of cells in a petri dish led to a decrease in the number of vesicles released per cell – suggesting either the cell-to-cell interface inhibits release of vesicles, or that neighboring cells are gobbling the particles up.

Researchers then used a technique that tagged donor cells – those releasing extracellular vesicles – with one color of dye and all other surrounding cells with a different color, and observed the vesicle activity at a single-cell level using flow cytometry. Results showed that the surrounding cells engulfed many of the vesicles and, in some cases, degraded them. Though any signal exchange was not measured, the results clearly showed that the vesicles didn’t stray very far from their donor cells.

“I was expecting we would see a huge exchange over a distance, and that no matter what, the vesicles would diffuse away, so the chance for being taken up nearby or far away should have been the same,” Cocucci said. “Instead, that seems not to be the case. When cells are close together, they share more vesicles with each other.”

To analyze what would happen in living tissue, tumors were developed in mice and then injected with one vesicle donor cell for every 3,000 acceptor cells, all dyed so they could be identified through confocal microscopy imaging. After introducing a chemical to prevent any degradation of the particles, the researchers measured how far extracellular vesicles dispersed from the donor cells.

The findings showed that 80% of the vesicles stayed within 40 microns – or 40 thousandths of a meter – of the donor cell, and 95% of these carriers traveled no farther than 70 microns away, a distance roughly equal to the thickness of a human hair.

Computational modeling predicted the same result.

“If we interpret this in a tissue situation, then donor cells will release vesicles, and the cells most affected by vesicle release are the surrounding cells,” Cocucci said. “When you go two to three cells away, these cells will affect the neighboring cells – suggesting that the majority of the effect of vesicles is constrained within 70 microns from the cell of origin.”

Cocucci’s lab is now developing tools for use in animal models that would allow the team to investigate and define the contribution of each tissue to the circulating pool of extracellular vesicles.

“If the release of the vesicle changes according to the physiological state of the tissue, this means the contribution of each tissue to the circulating extracellular vesicle pool changes according to the status of the tissue itself,” he said. “If you are able to define the contribution of each tissue in normal or disease conditions to the circulating pool of vesicles, then when we analyze vesicles from a patient, we may be able to suggest, without bias, a diagnosis without further analysis.”

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute, the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Ohio Cancer Research via the McCurdy/Kimball Midwest Research Fund, the American-Italian Cancer Foundation and a Pelotonia Postdoctoral Fellowship.

Additional co-authors were Federico Colombo, Kartik Nimkar, Erienne Grace Norton and Francesca Lovat, all of Ohio State.