Package deal: New faculty chromatin expert bridges pharmacy research and epigenetics

Your body is filled to the brim with genetic material. In one person alone, there is enough DNA to stretch to the sun over 300 times. All of that information is stored in our small human bodies thanks to the super-powered DNA protein-complex chromatin.

Chromatin is compacted DNA packaged up by proteins called histones. This packing of genetic material is essential to transcription, DNA replication, cell division, DNA repair and genetic recombination. In short, chromatin keeps our cells refreshed and our bodies functioning.

But what happens when disease states mess with chromatin regulation?

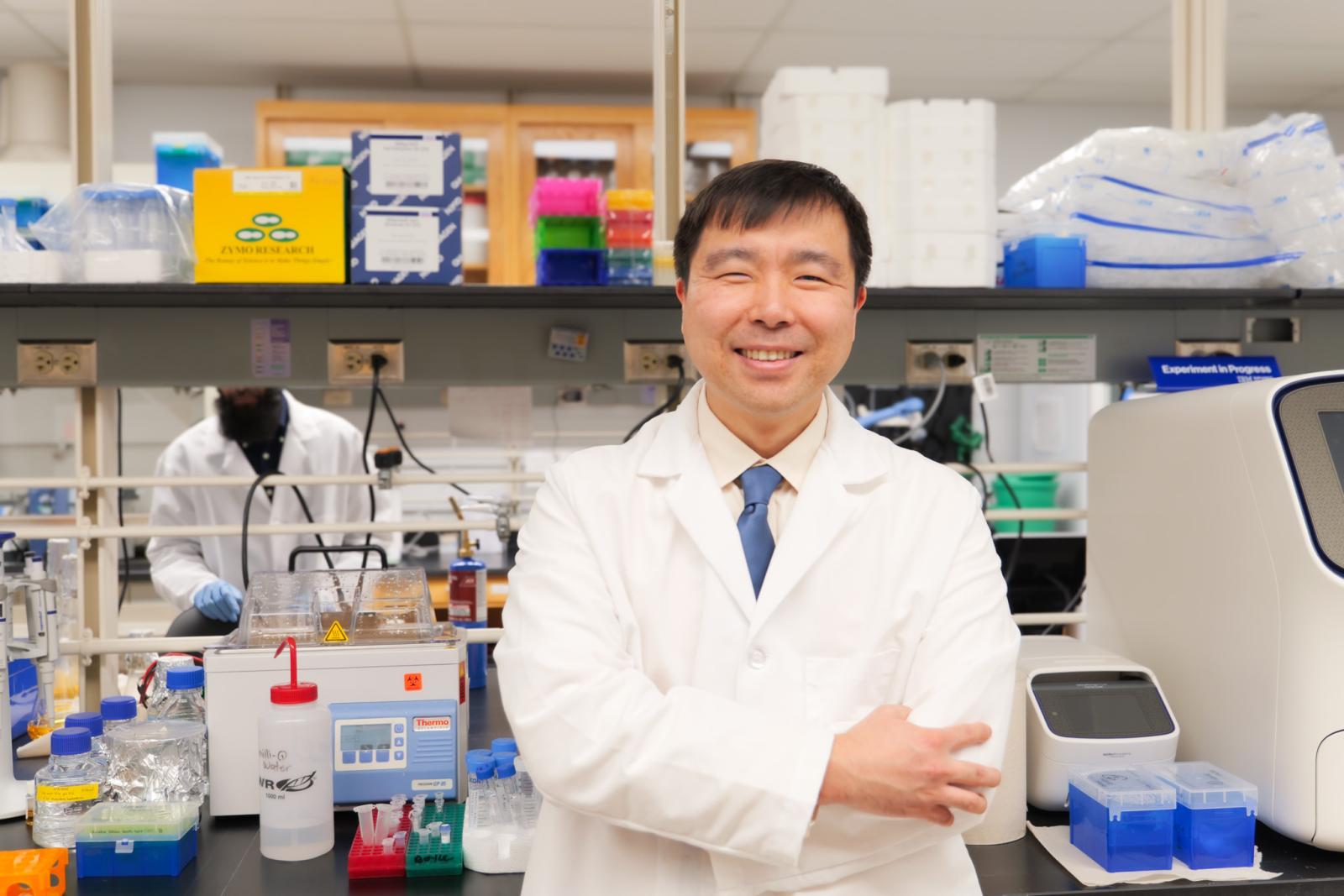

That’s a question that Kwangwoon “Jon” Lee, PhD, assistant professor at The Ohio State University College of Pharmacy, is hoping to answer. Dr. Lee joined the Division of Medicinal Chemistry and Pharmacognosy in July 2025 following a post-doctoral fellowship at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

“I love the Division of Medicinal Chemistry and Pharmacognosy because as other researchers discover and develop new drugs, I’m able to support their work. I’m here in part to help other researchers mechanistically interrogate how their designed therapies are functioning.”

Dr. Lee’s recruitment provides the college with new insight into epigenetics, a field that explores how gene expression can change without altering DNA sequences.

“It was through my postdoc that I became invested in chromatins as potential tools for epigenetic therapies,” Dr. Lee reflected. “On our team of chemical biologists, structural biologists and geneticists, I helped engineer enzymes to study how combinations of chemical modifications on histone proteins shape gene regulation in our cells. I built my understanding of chromatin and began to see it as a tool to assess and address genetic activity altered by disease states.”

Dr. Lee has established an exciting new lab since his appointment at the college. The Chromatin Design Lab team develops proteins and biosensors to study chromatin regulation and transcriptional control. By improving this understanding, they’re hoping to identify why chromatin regulation is disrupted in certain disease states and explore how associated proteins might be modified to fix it.

“One of our primary concerns is when disease states affect histones or other important components used by the chromatin to maintain regular genetic activity,” Dr. Lee explained. “When chromatin can’t properly serve its function, cells can lose normal control over which genes are turned on or off, setting the stage for uncontrolled growth and tumor formation.”

As the principal investigator (PI) whose research centers on protein biochemistry and chromatin regulation, Dr. Lee offers unique insight into the genetic aspects of medicinal chemistry research at the college.

“I love the Division of Medicinal Chemistry and Pharmacognosy because as other researchers discover and develop new drugs, I’m able to support their work,” Dr. Lee said. “I’m here in part to help other researchers mechanistically interrogate how their designed therapies are functioning. My team can confirm that these treatments are hitting target proteins and effectively engaging with those molecules.”

The lab is currently collaborating with Nationwide Children's Hospital on a project to investigate diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG). This rare form of fatal cancer in children ages 5-10 manifests as a tumor in patients’ brainstems.

The Chromatin Design Team is focusing on the commonly identified point mutation in DIPG patients, H3K27M. This mutation of histone H3 is considered a turning point in the disease when tumor cells become notably more aggressive and patient outcomes worsen.

“DIPG is well-characterized because many researchers are investigating why this form of cancer is so aggressive and looking for ways to treat it,” Dr. Lee explained. “As I learned more about it, I became curious about when the H3K27M mutation really matters. Is it only important early in tumor development, or does it continue to drive disease once the tumor becomes malignant? By applying the lens of epigenetics and chromatin biology, we’re trying to pinpoint the origin of this malignant activity.”

To root out this key mutation, the lab is crafting molecular tools made of proteins and peptides.

“In our lab, we’re designing an artificial protein that acts like a decoy, binding to the mutant histone before it can interact with the wrong partners,” Dr. Lee said. “By blocking these harmful interactions, the goal is to help restore normal gene control mechanisms and slow the growth of cancer cells.”

This approach allows the team to test whether the mutation continues to drive disease by disrupting gene regulation, even after tumors become fully malignant.

The method is somewhat unconventional, opting to build a protein-based inhibitor rather than a small molecule inhibitor, but Dr. Lee sees it as a promising method to halt harmful protein-protein interactions that spur DIPG.

“Currently, we’re walking the line between this inhibitor serving as a research tool and potential therapy,” Dr. Lee emphasized. “This is why I’m so excited to be at the College of Pharmacy. There are so many incredible collaborators whom I can learn from and work with to transition my current research tools into actual treatment.”